The Food and Drug Administration has multiple regulatory pathways for approving drugs, but one has been generating attention lately. A new report on orphan drugs from the Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) entitled “High-expenditure Medicare drugs often qualified for Orphan Drug Act incentives designed to encourage the development of treatments for rare diseases” caught my attention.

Here’s what the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 does: the orphan-drug designation gives drug manufacturers a seven-year exclusivity period per orphan indication and a 25% tax credit for expenses incurred during clinical trials, and waives New Drug Application fees (approximately $1.5-3M). Moreover, gaining additional orphan indications can extend the exclusivity period of those drugs even more. While designed to incentivize manufacturers to develop and run clinical trials for new drugs for rare diseases with small populations, it’s easy to see how the availability of these financial perks creates perverse incentives for manufacturers to seek out orphan designations for already-marketed drugs.

The Orphan Drug Act was enacted with the best of intentions and has had positive impact on patients with rare conditions. However, it’s time to take another look at what’s happening in this space in order to reward health care advances for patients without incentivizing bad behavior by some drug makers. Congress should reexamine the current system to limit orphan drug exclusivities to the true innovative drugs that are originally approved under an orphan indication. Reexamining who gets what and when from the Orphan Drug Act will allow for a more competitive marketplace and lead to lower overall drug costs. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) support innovation and will continue to promote affordable access of these medications for patients.

The proof is in the pudding: Over 20% of drugs with orphan indications (109 drugs) also have non-orphan indications, and more than half of those received the non-orphan indication first.

The OIG report is evidence that the Orphan Drug Act is not working as intended. OIG looked at the 20 drugs in Part B and Part D with the highest expenditures and found that 22 of these 40 were orphan drugs. Interestingly, 15 of those 22 orphan drugs also had approved non-orphan indications, making them partial orphan drugs (drugs approved to treat both rare and common diseases). And of those 15 orphan drugs, 10 – or a quarter of the original 40 high-expenditure drugs – received the non-orphan approval before the orphan indication approval. And for all but one of the partial orphan drugs, they were far more likely to be used for their non-orphan indications.

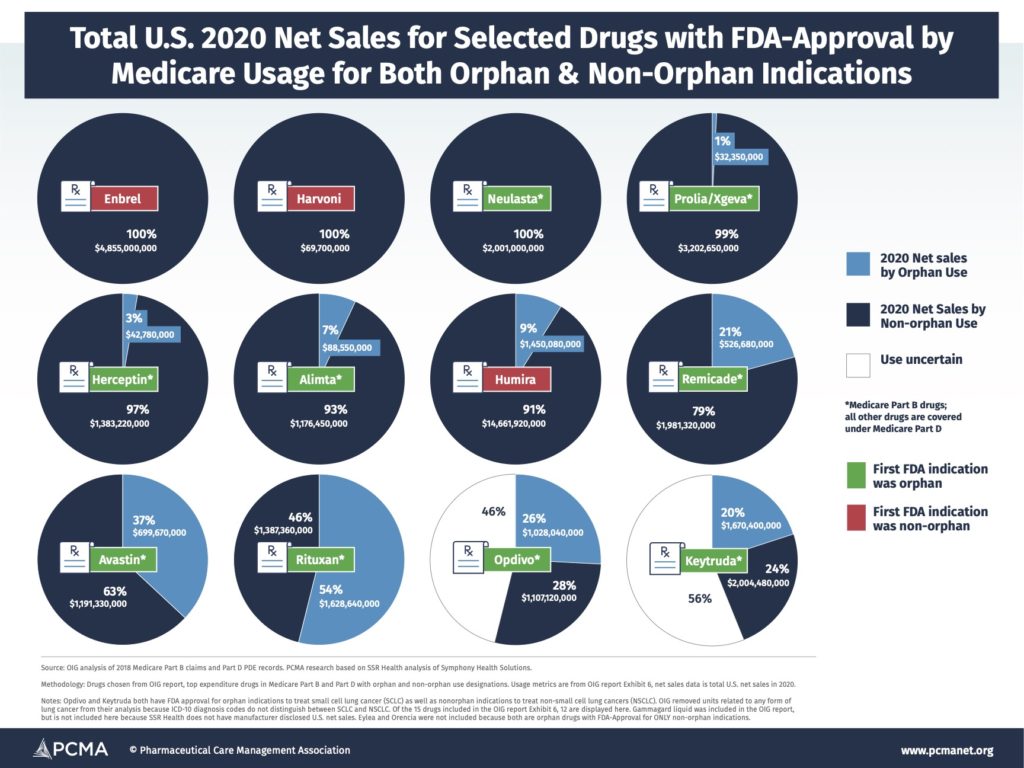

Combining the findings from OIG about orphan vs. non-orphan usage of a selected group of high-spending Medicare drugs with both orphan and non-orphan indications with total sales across all markets data for those drugs, you can see below (“2020 U.S. Net Sales for Selected Drugs with FDA-Approval by Medicare Usage for Both Orphan and Non-orphan Indications”) just how much money manufacturers make off of partial orphan drugs. (For more information on drug selection and assumptions around drug indications and usage see the OIG report.) Just one drug in the group had the majority of its usage related to its orphan indication. This means hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in sales for drugs that received benefits from the Orphan Drug Act aren’t actually for usage associated with that designation.